2013.03.06

Interview with Tohoku University Vol. 3

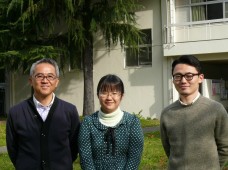

Not only does United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI) ask university executives to pledge their support for our principles, it also focuses on increasing students' understanding of the initiative's goals. At Tohoku University, UNIC Tokyo had an interview with two students involved in the Rapeseed Project.

Shiori Nasu, 2nd-year Master's student, Graduate School of Agriculture, Laboratory of Plant Breeding and Genetics

Ms. Nasu is involved in research to select highly salt-resistant rapeseed strains from Tohoku University's gene bank for the Rapeseed Project. When the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, she was on campus, feeling a massive tremor. In fact, two students from the Faculty of Agriculture were lost to the disaster.

After experiencing the disaster firsthand, Ms. Nasu, who had studied rice at the undergraduate level, decided to switch her research focus to rapeseed, whose potential was being explored for reconstruction purposes. "I am actually a slow starter when it comes to trying new things, but the disaster made me start to think about what new challenges I could tackle," Ms. Nasu admitted.

The Sendai City Agriculture & Horticulture Center where she conducts her research is a place where local residents congregated even before the disaster. She says many people who see her in her track suit picking and tending plants approach her out of curiosity. She shyly reveals that she is very happy when farmers tell her they, too, enjoy growing the same plants as her. It is evident that her feeling of contributing something to the local community gives meaning to her work.

Daisuke Arai, 1st-year Master's student, Graduate School of Agriculture, Soil Science Laboratory

After graduating from a university in Kanagawa Prefecture, Mr. Arai decided to attend graduate school at Tohoku University because of the many soil science experts there. Initially, he had no intention of conducting research related to disaster reconstruction, but slowly a desire to help Japan's farmers welled up, and he chose post-disaster salt removal as his research topic.

In fact, the soil damage caused by the tsunami in Tohoku is unprecedented in its scale. "Tsunamis that cause salt damage to the soil on this scale only happen once every 1,000 years. In other words, the samples we take are academically invaluable, and our research may reveal something new," explained Arai enthusiastically.

Arai says that even students enrolled in the Faculty of Agriculture do not actually have many opportunities to conduct research in rice paddies and fields. They are more likely to spend the whole day in the lab analyzing soil samples from overseas. but At Tohoku University, however, practical work on reconstruction efforts are given priority, enabling students spend more time in the field. This naturally increases connections to the community, and that is what seems to make this research rewarding for young scholars like Mr. Arai.

On the other hand, the job of a researcher also has its troubles. "Last month I gave a presentation in Iwanuma City. It was open to the general public, but while many experts attended, no local citizens participated", said Arai disappointedly. His presentation was on an experiment that would allow farmers remove salt using only rain water without the aid of special machinery or materials. "I really wanted the local citizens to hear my presentation. Maybe some people have thought that the topics we researchers deal with are too difficult," speculated Arai.

Both Ms. Nasu and Mr. Arai said there is something they want to try if the rapeseed they planted proves effective in removing salt from the soil. While they are currently using highly salt-resistant varieties of rapeseed for the Rapeseed Project, they want to start growing plants that are less resistant. Their eyes sparkled as they explained that southern Sendai used to be famous for growing strawberries in greenhouses, so they would like to plant strawberries like farmers used to before the disaster.

After talking to these students, Prof. Nakai concluded with a memorable remark: "Our research has to attempt to achieve two things simultaneously. First, it must be advanced research that can withstand the rigors of the scientific community. But this forces us to separate ourselves from the farms on the ground. At the same time, our research must seek to understand what farmers are doing, so we can provide them with assistance as soon as possible. Like two wheels on a cart, we must keep both of these goals in balance as we move forward."

Listening to Ms. Nasu and Mr. Arai, you start to understand how much university research has been contributing to regional reconstruction in the wake of the disaster, because these two young researchers, like the "two wheels" that Prof. Nakai mentioned, have already started to move ahead together.

* * * * *

最近の記事

-

2024.05.08

世界報道自由デー(5月3日)に寄せる アントニオ・グテーレス国連事務総長メッセージ -

2024.05.08

エネルギー移行に不可欠な重要鉱物のバリュー・チェーン全体にわたる公平性、持続可能性、人権に取り組むパネルを国連が招集(2024年4月26日付プレスリリース・日本語訳) -

2024.05.08

ある日本の町、資源循環型社会への道をひらく(UN News 記事・日本語訳) -

2024.04.26

国連経済社会理事会(ECOSOC)ユースフォーラム2024におけるアントニオ・グテーレス国連事務総長発言(ニューヨーク、2024年4月16日) -

2024.04.26

国連の新たな報告書、SDGsを救うための数兆ドルの開発投資の拡大を呼びかけ(2024年4月9日付プレスリリース・日本語訳)